Santarém

Filipe Castro, Clara Brito, Rui Falcão de Campos and Miguel Soares Lopes

Introduction

This project started when a number of mid-19th century boats were exposed in Lisbon, in the place where the old Cais de Santarém was located, during the construction of a subterranean parking lot [see below].

The importance of Santarém as a fluvial and maritime landscape is not sufficiently studied, but the circumstances of its location, on a protected hill, looking over one of the most fertile plains in western Europe, and on the margins of Portugal’s largest river have inspired this study.

As with all the projects on this website, this one is intended to fuel the curiosity and interest of a wide public, both professional and amateur, and link it to scholarly publications and other projects that may be of interest to Santarém’s inhabitants, tourists, and scholars studying the last 28 centuries.

History of the Village

Probably built over a pre-historic settlement, the earliest archaeological remains date to the 8th century BCE and are related to the Phoenician occupation of the Tagus Estuary.

Excavations in the castle revealed a Roman temple and well preserved Roman ruins from the republican period. Romans seem to have arrived in Santarém around 138 BCE, calling it Scalabi Castro. After the conquest of Iberia by Julius Caesar, around 60 BCE, the city was occupied by a stationed army, changing its name to Praesidium Juliia. It may have been fortified in this period. The road connecting Lisbon to Astorga passed by Santarém and there are archaeological remains of this structure in Vale de Santarém, at Quinta do Malpique (Endovélico Ref. 7,347). The imperial strata were deeply impacted by the Arab occupation of the castle.

During the 5th century the Iberian Peninsula saw a pronounced decadence of the cities, the elites, and the civic activities. Invasions by Alans and Vandals probably impacted the city, which was eventually given to Roman general Sunieric, who conquered it with a Visigothic army (c. 460 CE). Santarém was conquered by the Suevi in 529 CE and later, in the 7th century, by Visigoths. During the period of the Visigothic invasions Scallabis was named Sancta Irene (or Iria).

It seems that Sancta Irene did not suffer most of the wars and violence that characterized the period of desegregation of the Roman order. Vandals, Alans, Suevi and Visigoths invaded the Iberian Peninsula and sacked and destroyed many of the most important cities.

There is not a lot of information about the city during this period, although the organic layout of the streets over most of the city suggests the destruction of the Roman village and a rather disorganized growth of the city before and during the Islamic occupation.

In 714 it was conquered by a Muslim army. The early city – now known as Shantarîn – may have been located in the alcáçova area, with a small neighborhood to the northeast, outside the walls, named Alcúdia, and another to west of Alcúdia, named Alpram. The original necropolis may have been located near Alpram. During the 8th and 9th centuries the alcáçova area was walled and reinforced with towers, and the city grew to the north, into the Marvila hill.

In the 11th century a new mosque was erected near the city’s sûq. By now the city had grown to 3,500 inhabitants and the main area was walled. The new necropolis was located on the west plateau. A new neighborhood to the north of Alcúdia, named Seserigo, connecting the higher city to the fluvial area and a wall is built to protect the new road of Atamarma. During this period a new neighborhood named Alfansi developed in a secondary waterfront area, and connected directly with the alcáçova through a steep road that ended at Porta do Sol and another that ran around the western city walls.

When the Christian invasions reached its surroundings, Shantarîn was a prosperous small city, surrounded by orchards, gardens, vegetable gardens, and vineyards. In the late 11th and early 12th centuries this relatively small city was conquered and lost by Christian warlords from Spain, and finally conquered in 1147 by Afonso Henriques, the first king of the newly created kingdom of Portugal.

The City

Today Santarém is a small city of about 30,000 people but it was once a prosperous center. A series of political miscalculations (1824 and 1384), a tragic accident (1491), and three violent earthquakes (1531, 1755, and 1909) and kept Santarém from fully developing its political influence.

The city location and the wealth it accumulated made Santarém a monumental city, perched over the Tagus River, one of the most important arteries of the country throughout its history. An important part of its monuments still stands, sometimes relatively preserved, sometimes destroyed and reconstructed several times, and sometimes incorporated in more modern buildings, its walls reused for new functions in the constant evolution of the city life.

Cities are in constant evolution. Progress, fires, natural disasters such as earthquakes, war, economic crisis, and urban policies affect the way buildings are kept, abandoned, bought, rebuilt, how traffic flows and how people perceive their habitat and feel about it. If we look close, many aspects of the lives of the people that made Santarém over a period of 28 centuries are attached to the city’s buildings, roads, gardens. History is the soul of a landscape, and the objective of this website if to try to make sense of the stories that made Santarém, based on historical and archaeological data.

We are trying to develop a GIS map of Santarém, organize the archaeological finds chronologically, and share the city’s history here. It is not easy to reconstruct Santarém. Change is a dynamic process. As mentioned above, erosion, earthquakes, fires, wars, economic cycles, all impacted the city’s organic growth and the mentality of the people that lived and died in it.

The first step of such a project is a good assessment of the city’s material culture, from the Iron Age archaeological remains to the latest building, from the municipal edicts prohibiting the population from cutting the vegetation on the slopes around the old castle to the engineering works of the 20th century, illustrating the city’s long fight against the erosion of its slopes.

We are trying to inventory the city’s walls, doors, and towers, the roads and fluvial routes, the city’s water supplies, its convents, churches, palaces, houses, shops, roads, and gardens.

Below are presented some summary descriptions of some of Santarém’s most interesting constructions and spaces, or memories. We have divided the city spaces as public and private, secular and religious:

Secular public spaces – Walls, doors, towers, roads, passages, squares, markets, and empty grounds; administrative spaces, and meeting places; commercial spaces such as shops; entertaining spaces such as theaters.

Secular private spaces – Industrial spaces such as kilns, workshops, wine production facilities, and storage buildings; elite domestic spaces; and non-elite domestic spaces.

Religious public places – Temples, mosques, synagogues, churches, and chapels (ermitas).

Religious private places – Monasteries, convents, tombs, and altars.

City Walls, Doors, and Towers

The historic center of Santarém is clearly visible in the maps, and the shape of the walls that protected the village over the centuries can still be reconstructed along most of its extension. Over time some of the doors and towers became old, or encumbered the city life and were demolished, or changed, or incorporated in newer buildings.

The Walls

Santarém was fortified probably already in Roman times, and certainly during the Arab occupation. Its walls were expanded, demolished and rebuilt several times, and it is not easy to reconstruct the several walls built over time.

The Doors

Most of the city’s old doors were demolished to let the carts, and then the cars into the historic center. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries a number of these constructions were old and difficult to repair, and the city council saw them as obstacles to progress. A few survive, however, and we have a general ideal of the positions of others.

The Towers

Most of the towers mentioned in historic documents or deduced to have existed in the areas of the city doors have been demolished, for various reasons. Some were incorporated in other constructions, and a few are still standing.

[more]

The Bridges

Ponte de Alcource – This bridge was built in the middle age, probably in the 14th century, and possibly to replace an early Roman bridge that may have existed in this place. It spans the Vala de Palhais and was part of the road from Santarém to Coimbra.

As the landscape changed considerably during the last two millennia, it is difficult to reconstruct the path of the Roman road, or even to assert if this bridge was at all part of a Roman road.

Ponte D. Luis I– Was inaugurated in September of 1881. At the time it was said to be the third largest in Europe and sixth in the world. At the time of its construction it was considered an achievement in the field of civil engineering.

The river crossing was done by boat, and this activity is referred in the historical record. Today there is no port in Santarém, almost no boats, as the access to the river was cut by the railroad in the beginning of the 20th century. Before disappearing, the traditional fishing village was located downstream at a place called Caneiras, slightly downstream from the new A13 bridge.

Ponte da autoestrada A13 – This bridge is part of a highway built in the early 21st century and is part of a late 20th century infrastructure plan.

Water Supply

Almost completely destroyed and forgotten, a number of subterranean channels seem to have been cut under the city and on its northern area. There are mentions of several of these tunnels, for instance, near Vale de Estacas, deemed dangerous for children and destroyed by the military, with a bulldozer, in the early 1970s. More of these tunnels were located, namely in Ribeira de Santarém, when one of these tunnels collapsed and three were exposed by engineering works (Ref. 33,933); and at Mãe d’Água, an old building located on a slope near the old Convent of Santa Clara, and from which three water tunnels enter under the hill.

Cisterns

Most monasteries and several houses had underground cisterns, and several are still in existence. We have inventoried ten so far, of which one was just reported at the time of its destruction, in the foundations of one of five buildings of Avenida 5 de Outubro.

A collection of coins found on this last cistern was partly donated to a museum in Coimbra and is inventoried, although we have not been able to locate it yet.

[more]

Mãe d’Água

This old building has not deserved enough archaeological attention and it is difficult to find bibliography detailing its age and functions. In the 1970s it was used to keep sheep during the night, and was eventually abandoned and covered with vegetation. In 2012 the municipality cleaned it from the vegetation. This site dates probably from the Arab occupation and was possibly associated to an aqueduct that transported water to the old castle.

Fountains

A number of old fountains still exist, or are known to have existed in Santarém.

Fonte das Figueiras – This fountain dates to the late 13th or early 14th century and was designated national monument and probably conserved in the early 20th century.

To our knowledge, its surrounded area has not been excavated. It is located in an area of the city that has very few traffic and perhaps for that reason, it is in a fairly good condition.

We know that it was once located within the perimeter of the wider walls, built to protect the area closer to the river.

Chafariz de Palhais – Built in the late 18th century, on the old road to Coimbra. There was a church in this area – Santa Maria de Palhais, and it is likely that there was an older fountain in the place of this one.

The small church (ermida) of Santa Maria de Palhais was part of an old hospital. At this point we do not have yet the dates in which the hospital and church were built and demolished.

Palaces

The most important palaces in Santarém were the old alcáçova palace, and the later royal palace, situated where now is the Seminary. Both these constructions have long been demolished.

A number of rich houses were built over the 28 centuries of the city’s existence. The most important standing is the palace – Eugénio da Silva – were today is located the municipality.

Palácio Eugénio da Silva

Built in the late 17th century outside the city walls by the Meneses family, its facade looked upon Largo do Espírito Santo.

Palácio Landal

Tradition places the birth of D. manuel de Souda Coutinho in 1555, a writer known as Frei Luis de Sousa.

Temples, Mosques, Churches, and Chapels

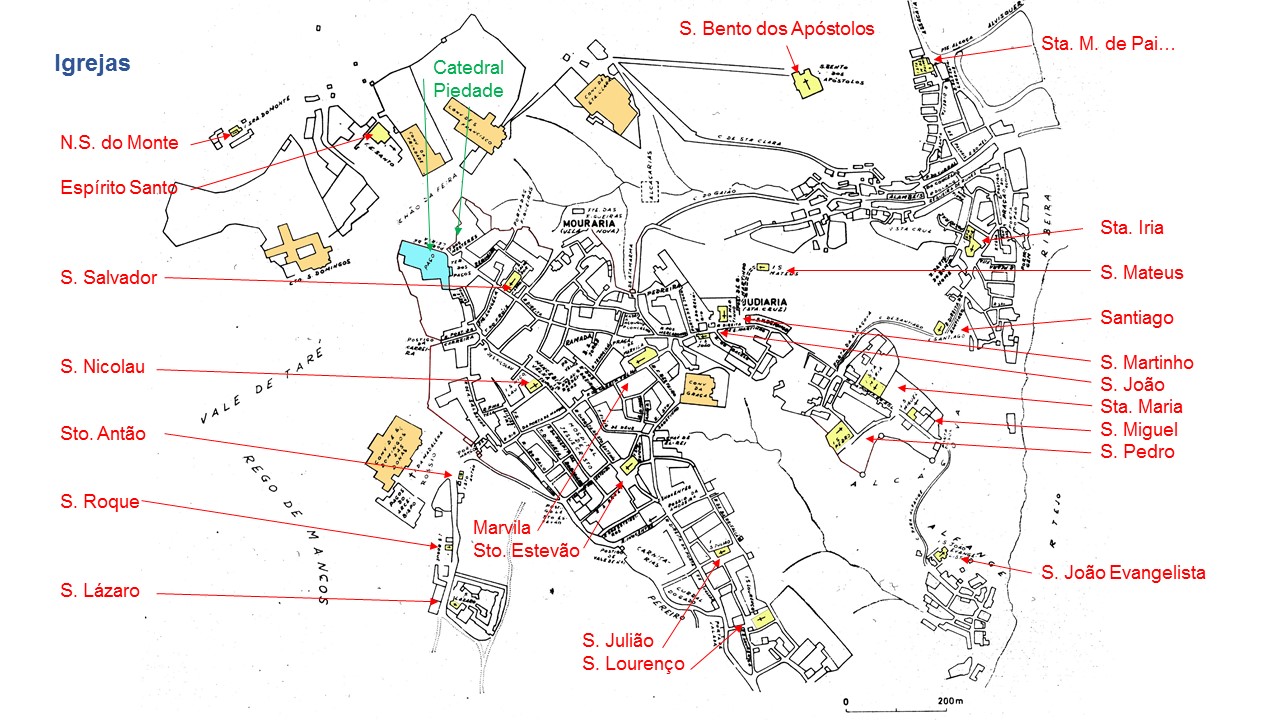

There is not a lot of information about locals of worship in Santarém prior to its conquest. The remains of a Roman temple have been surveyed in today’s Jardim das Portas dos Sol, the church of S. João Evangelista seem to have been built over a previous Visigothic temple, and scholars believe that the city’s mosque was located in the place where now stands the church of Marvila. In spite of its small population, Santarém had a large number of churches.

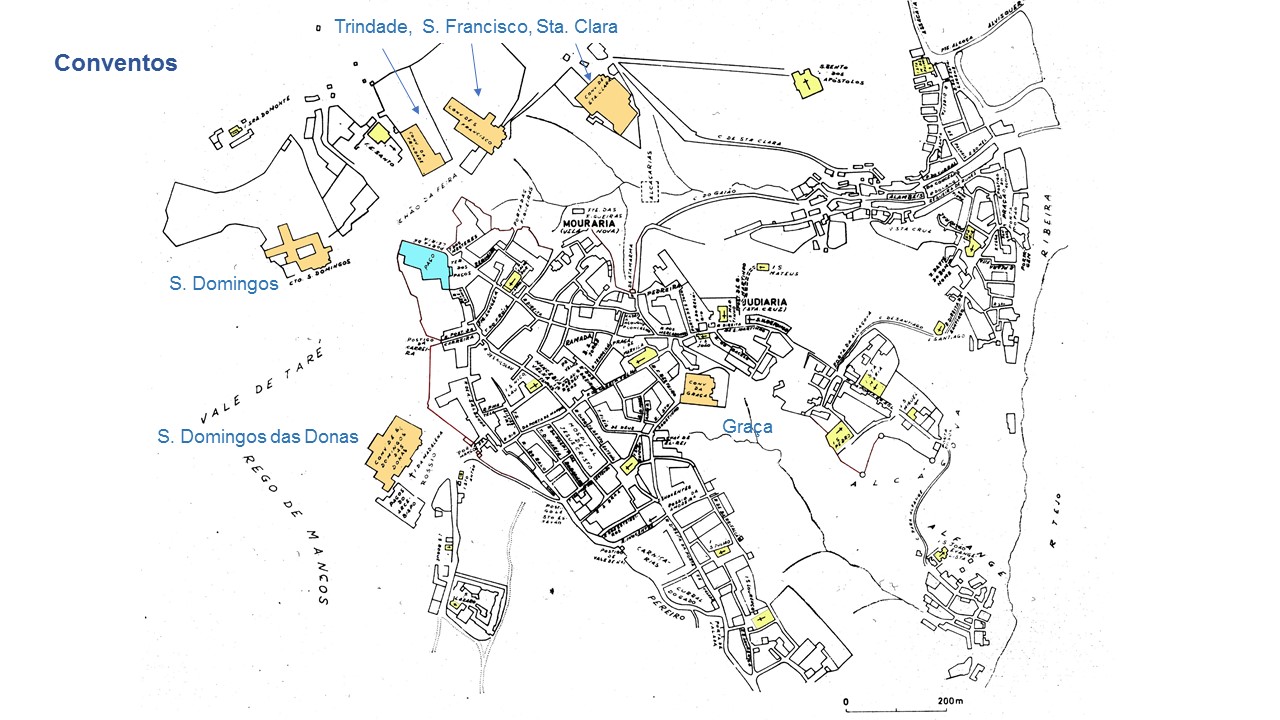

The Convents

Santarém was the most important center of a very rich agricultural center and its fertile soil maintained a number of religious orders.

There is an extensive record of purchases, sales, and donations of orchards and planted fields that provided for the religious orders established in Santarém after the conquest, in 1147. [more]

Submerged Structures

In September 2010 a team of firemen was rescuing some lost equipment and found submerged structures with ceramic materials associated (Ref. 37370) near the S. Luis I Bridge. These structures have not been surveyed by archaeologists, although there is a video of the site (which we have not been able to locate).

The Fluvial Landscape

Developed near the River and depending on it for transport, irrigation, and the annual floods that fertilized of the soils from which its wealth depended, Santarém was a fluvial landscape above all.

The River Tagus meanders through its alluvial plain and is constrained by the hill upon which Santarém was built. The city had expanded down hill at least by Roman times, and remains of medieval walls remind us that part of the the port area was protected from possible enemy attacks.

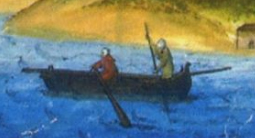

Historical documents suggest that Santarém had an intense fluvial traffic, encompassing routes to and from Lisbon, and upstream from Santarém, possibly up to Almourol. Boats from Ribeira de Santarém also engaged in the daily river crossing activities, and it is likely that this part of the village harbored an intense fishing activity, which lasted well into the 19th century. The ships from Santaré are referred by father Manuel Fernandes’ Liuro da fabrica das naus (c.1580), on the late 16th century: “Os barcos de Santarém levantam agora mais as cabeças, e mudam os nomes de cervilhas em muletas: isto de quatro dias para cá: pois vede a mudança, que será feita de cento, ou duzentos ou mais anos a esta parte: e como são já esquecidos os nomes, e mudadas as formas dos navios daquele tempo, e mais atrás.”

The early 16th century view by António da Holanda shows a busy river harbor with small, road boats, and middle sized watercraft with lateral rudders and lateen sails. Some of the crew members are maneuvering the boats near the shore with punts.

Empty spaces on the water front were needed for shipbuilding, loading and unloading, equipment storing and repairing, and perhaps also shacks for fishing and repairing tools. The beaches showed in António de Holanda’s view are still partly empty today, but to our knowledge there have never been archaeological surveys in the area.

An interesting detail in this view suggests that a boat is being pulled upstream with a rope, which seems to be uncommonly tied to the top of its mast.

An important feature on this waterfront is the 17th century shrine to Santa Iria, a legendary medieval nun falsely accused of being pregnant whose body washed ashore at Santarém after being assassinated on the margin of Zêzere River, one of the tributaries of the Tagus.

This legend had already inspired the construction of the church of Santa Iria, around the 12th or 13th centuries, already mentioned above.

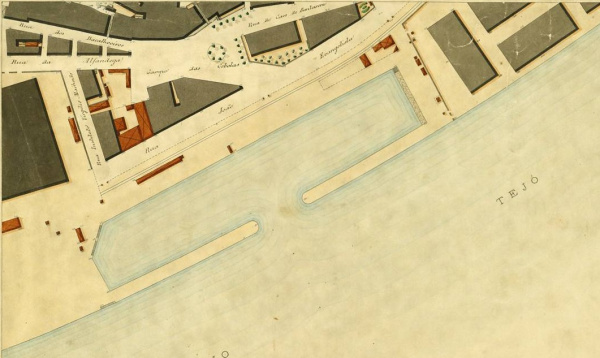

“Cais de Santarém” in Lisbon

In 2016 and 2017, the construction of a subterranean car park, in the area of the old Cais de Santarém, brought to light eight boats dating to the mid 19th century. These boats attest an old sailing tradition between Lisbon and Santarém, which is not very well studied yet.

The waterfronts, both in Lisbon and Santarém have changed almost continuously since the Middle Ages, and there are – to our knowledge – no studies of the infrastructures built to load and unload the boats that connected these two cities.

[more]

References

(we have not yet acquired some of the titles mentioned below)

Almeida, Maria José, 1998. Intervenção arqueológica no Miradouro de S. Bento, Santarém. Report available at academia.edu.

Almeida, Maria José, 1999. Intervenção arqueológica na Rua tenente Valadim No. 14, Santarém. Report available at academia.edu.

Almeida, Maria José, 1998. Intervenção arqueológica na Rua de S. Martinho No. 17-12, Santarém. Report available at academia.edu.

Cardoso, Mário, Almeida, Maria José, Mendes, Henrique Calé, 2002. “A Porta da Atamarma,” in Isabel Cristina ferreira Fernandes, ed., Mil Anos de Fortificaçoes na Península Ibérica e no Magreb (500-1500), Simpósio Internacional sobre Castelos, 2000. Lisboa: Ed. Colibri e C. M. de Palmela.

Almeida, Maria José, 1998. Intervenção arqueológica na Rua dos Barcos, Travessa da Oliveirinha, Ribeira de Santarém. Report available at academia.edu.

Almeida, Maria José, 1997. Relatório de Acompanhamentos Arqueológicos no Centro Histórico de Santarém. Report available at academia.edu.

Almeida, Maria José, 1999. Relatório de Acompanhamento Arqueológico no Centro Histórico de Santarém. Report available at academia.edu.

Almeida, Maria José, 1997. Intervenção arqueológica na “Casa do Brasil,” Rua Vila de belmonte No. 13-15, Santarém. Report available at academia.edu.

Almeida, Maria José, 1998. Carta arqueológica do Concelho de Santarém – Doc. Preparatório. Report available at academia.edu.

Almeida, Maria José, 2002. Carta arqueológica do Concelho de Santarém – Rel. Progresso. Report available at academia.edu.

Almeida, Maria José, 1998. Intervenção arqueológica no largo Zeferino Sarmento / R. Conselheiro F. Leal, Santarém. Report available at academia.edu.

Almeida, Maria José, 2002. “Museu Arqueológico de S. João de Alporão, Santarém,” in O Arqueólogo Português, 4.20: 191-198. Available at academia.edu.

Arruda, Virgílio, 1962. “As muralhas de Santarém,” Correio do Ribatejo, Santarém, 29 Dezembro.

Beirante, Maria Ângela, 1980. Santarém Medieval. Lisboa: Universidade Nova de Lisboa.

Beirante, Maria Ângela, 1981. Santarém Quinhentista. Lisboa: Livraria Portugal.

Brandão, Zephyrino, 1883. Monumentos e lendas de Santarém. Lisboa: .

Braz, José Campos, 2000. Santarém raízes e memórias – páginas da minha agenda. Santarém: Santa Casa da Misericórdia de Santarém.

Cardoso, Mário de Sousa, 1979. As Muralhas de Santarém e a sua evolução. Santarém: .

Custódio, Jorge, 1996. Património Classificado de Santarém (texto policopiado). Santarém: .

Custódio, Jorge (coord.), 1996. Santarém Cidade do Mundo, vol. I e II, Santarém, Câmara Municipal de Santarém.

Custódio, Jorge (coord.), 1996. Património Monumental de Santarém : Inventário – Estudos Descritivos, Santarém, Câmara Municipal de Santarém.

Feio, A. Areosa, 1929. Santarém, princesa das nossas vilas. Santarém: .

Matoso, Luis Montes 2011. Santarém Ilustrada. 2. Ed. Santarém: Junta de Freguesia de Marvila.

N/A, 1998-2000 e 2005. “Vária”. Monumentos. n.º 9 a n.º 12 e n.º 23. Lisboa, DGEMN.

Ortigão, Ramalho, 1903 (1896). O Culto da Arte em Portugal. Lisboa: Aillaud e Bertrand.

Rodrigues, J. Delgado e Castro, Guy de, 1979. Parecer sobre as obras de protecção da escarpa e das muralhas de Santarém sobre o caminho do Alfange. Lisboa, LNEC – DGEMN.

Santos, Isabel Claudino, 2018. Arquivo Histórico da Câmara Municipal de Santarém. Dissertação de Mestrado, Fac. de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa.

Internet

https://www.cm-santarem.pt/descobrir-santarem/o-que-visitar

http://www.santaremdigital.com.pt/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=89&Itemid=83 [17-04-2009];

http://www.patrimoniocultural.pt/pt/patrimonio/patrimonio-imovel/pesquisa-do-patrimonio/classificado-ou-em-vias-de-classificacao/geral/view/72656 [consultado em 28 dezembro 2016].

https://toponimialisboa.wordpress.com/category/cais/ (accessed Oct 2019).

http://aminhasantarem.blogspot.com/p/textos.html (accessed Dec 2019)